Here comes Field Day and all of your careful equipment connections and filtering go out the window as the station is disassembled and hauled off to the operating site. Be aware that operating in a multi-station environment, like the popular 2A category, requires that all of the transmitters be “clean.” That is, transmit a minimum of spurious emissions like harmonics, intermodulation products, and the bugaboo of wideband noise.

One “bad apple” can really be aggravating, so here are a few techniques you can use to keep the peace.

If you want to know more about interstation interference, one of the best references is “Managing Interstation Interference” by W2VJN. It’s available as a PDF download here from Vibroplex. It covers filters, stubs, and other techniques.

Lightning Protection

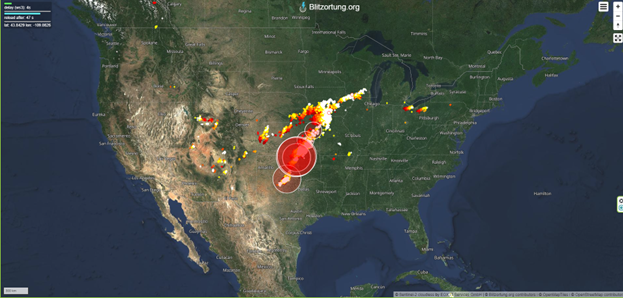

Before we discuss noise, let’s start with the understanding that lightning protection is pretty much impossible for a portable station. Your ground system will be temporary and very lightweight. A ground rod or two just won’t do the job either. What to do? When lightning is in the area—say, within five miles—that’s the time to lower your antennas, disconnect the feed lines and power cords, and get away from the equipment. A lightning detector, such those available from Weather Shack or other vendors, is a good idea. Lightning monitoring apps such as www.blitzortung.org (below) are available for smartphones, tablets, and PCs.

When you disconnect feed lines, move them at least six feet away from any equipment and preferably a lot farther. Wait until the lightning has moved on before reconnecting your station.

Wideband Noise

The most common noise problem encountered on Field Day is wideband noise from a transmitter. Depending on the transmitter’s structure, the noise might be limited to the frequencies near the transmitted signal, just to the band of the signal, or across several bands. The cause is almost always noise on the oscillator(s) in the transmitter.

Noise close to a transmitted signal covers up weak signals on adjacent frequencies. As the noisy transmitter tunes closer to your listening frequency, you’ll hear the noise floor increase whenever the transmitter is keyed, independent of output power. Similarly, noise will also be present on harmonics of the transmitted signal.

Wideband noise that occupies an entire band or several bands is the biggest problem for multi-station Field Day setups.

How can you tell if your transmitter is generating this type of noise? Don’t worry, operators at the other stations will tell you! Right away! Because all of the stations are so close together, the transmitted noise may make it impossible to operate.

Field Day managers should make sure that any on-site transmitter is well-behaved. Conduct a test of your radio before Field Day. Get on the air with a ham close by or have a ham with a portable receiver listen on all of the bands from several hundred feet away. If they can hear noise when you close the PTT switch, your radio has a problem.

This type of noise must be filtered at the transmitter. Once radiated, it cannot be filtered out at the receiver because it is the same as any other “in-band” signal.

Band-pass filters, such as the LP-BPF-20 filter from VA6AM Engineering below, are good practice for all stations but an absolute necessity for transmitters that generate wideband noise. A set of band-pass filters for the HF bands is a good club purchase! QRP filter kits are also available, and there are a number of schematics available online if you want to build some from scratch.

Even with a filter, other stations on the same band, such as a 75 meter phone and 80 meter CW or FT8 station, will experience interference from the noisy transmitter.

The best solution to wideband noise is to not generate it in the first place. Test all transmitters before Field Day and leave the noisemakers at home. Be aware that you may be completely unaware that you have a noisy transmitter. After all, you probably aren’t receiving while you’re transmitting!

Harmonics & Intermodulation (IMD)

Every transmitter generates some harmonics. They are mostly quite weak but when you are operating more than one station in close proximity, they are strong and can cause a lot of problems. Like wideband noise, harmonics must be filtered out at the transmitter. A band-pass filter will work, or transmission line stubs can knock down harmonics.

Even with filtering, you probably won’t be able to completely suppress harmonics. It’s a good idea to agree ahead of time on a plan to adjust operating frequencies to avoid interfering with another local station. For example, if the 20 meter station is going to operate on 14220 kHz, the 10 meter station needs to avoid 28440 kHz and nearby frequencies. Coordinate frequencies—it’s better than arguing about who’s interfering with who!

Another source of QRM is intermodulation in the transmitter or amplifier. Often a problem on phone, the different speech components mix together in the RF power devices and generate many signals outside the desired bandwidth of the output signal. This generates “splatter” and “buckshot” on nearby frequencies.

You can reduce these unwanted signals by careful adjustment of your microphone gain and any speech processing. Before Field Day, have a nearby ham listen to your signal on a quiet band as you adjust the transmitter for the cleanest, full-power output. Take note of the settings so you don’t have to repeat the exercise on Field Day.

Key-clicks and audio IMD on digital signals are also sources of in-band interference to adjacent signals. Solid-state amplifiers are particularly susceptible to overdrive above about half their rated power output. Be a good neighbor and make sure you have signal rise-time and amplitude settings right for the best-sounding signal on adjacent channels. Run amplifiers at reduced output power to avoid generating “spurs” as well.

The ARRL is addressing these problems through the Clean Signal Initiative. As this program progresses, look for more information about how to ensure your transmitter is properly adjusted. In addition, there will be methods for comparing and evaluating signals.

Passive Harmonic Generators

Be aware that strong RF picked up on feed lines and control cables can be conducted into equipment by shields or unshielded conductors. Once inside the equipment, if the RF encounters any diodes or rectifiers (or LED indicators!) it will be partially rectified and many harmonics generated. Those harmonics go right back out by the same path and are radiated as interfering signals.

These can be hard to troubleshoot and resolve during the short Field Day period. It may be best to simply take the minimum amount of equipment you need. Ferrite snap-on cores can be effective if you can determine which cables and equipment are causing the problem. Type 31 material is the best for HF use.

Receiver Overload

What sounds like wideband interference can often be caused by receiver overload from the strong signals of nearby transmitters. Turn off Noise Blankers, which respond to strong signals by trying to turn off the receiver during what they think is a noise pulse. This can result in what sounds like a transmitted signal “clobbering the whole band.” Turning on a preamp can result in the same problem.

Overload generally disappears as RF Gain is reduced below a threshold. You can give your receiver a little breathing room by switching in some attenuation. You’ll still be able to hear the other signals and the band may sound a lot cleaner. Only use the minimum amount of gain needed. Band-pass filters can also be used if an out-of-band signal is causing the overload.

Bonding to Prevent RF Problems

Within the station, you can help reduce harmonics and spurs by making sure all of the equipment is well-bonded together. This is particularly important if you are running an amplifier. RFI from a transmitted signal is generally caused by significant voltage between pieces of equipment. This is often a result of having antennas very close to the station, as is typical of Field Day setups. RF “hot spots” at high-voltage points are created by the same RF current.

You can address these problems with bonding—connecting equipment together to minimize voltage differences. This topic is covered in more detail by my 2022 OnAllBands article, “Grounding and Bonding for Portable Amateur Radio Stations.”

You may be surprised to find that a simple sheet of aluminum foil and some clip leads can solve a lot of RF problems!