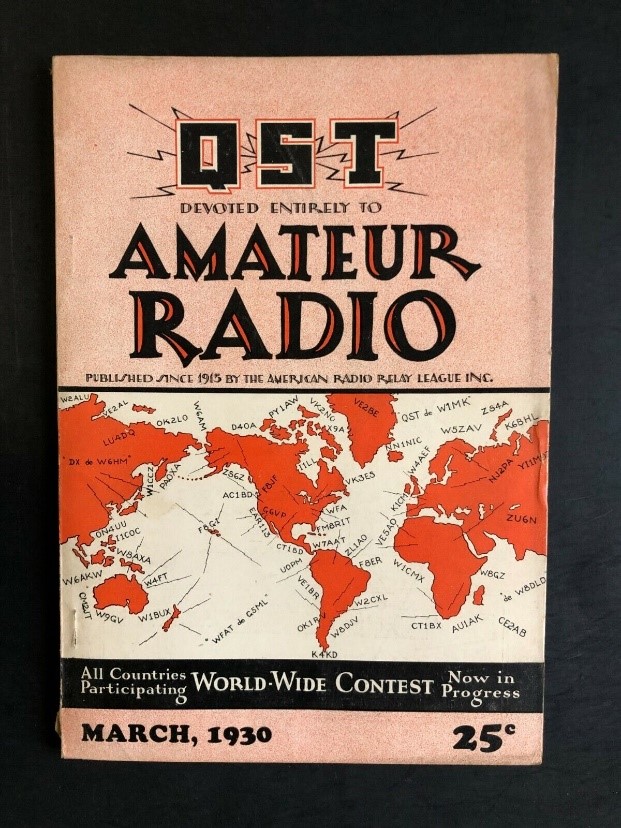

In just two weeks (February 17-18) one of the biggest CW contests in the world will fill the bands from 160–10 meters (except for 60, 30, 17, and 12 meters, of course). The ARRL International DX CW Contest is also amateur radio’s longest-running contest with the first “International Relay Party” held in 1927. (The first ARRL DX Phone was held in 1937. The second oldest contest is the ARRL Sweepstakes, first held in 1930.)

The ARRL noted in 2010 that stations in the US and Canada work only DX stations—Alaska and Hawaii are considered DX for this contest—and DX stations only work the US and Canada. DX stations will be trying to make QSOs with all US states and Canadian provinces. The contest exchange is simple: US and Canadian stations send a signal report and their state or province, while DX stations send a signal report and (their transmit) power.

“If you’ve never operated the CW contest, now is the time to start,” former Contest Branch Manager Sean Kutzko, KX9X, said. “You can work a lot of DX with 100 W and a simple dipole or vertical antenna. If your CW is a little rusty, this event is a great way to get your CW skills back up to snuff and get some new DX countries into your bag. If you live in one of the rarer states—such as Delaware, North Dakota, West Virginia or Wyoming—DX stations from all around the world will be looking for you. This is your opportunity to ‘be the rare one!’”

ARRL DX is kinder to “little pistols” than the CQ World Wide contests because the DX stations can only work the US and Canada—no trying to crack a big pileup of Asian stations calling Saipan (KHØ) or Europeans with a pipeline to Senegal (6W)! By now, you’re probably thinking, “This sounds like fun!” and you would be right. Time to limber up the paddle and see about filling your log with some new band-countries. There will be lots of opportunities! See the appendix at the end of this article to learn what you need to get started.

(Although N1MM+ takes some effort to configure and use, it is the most popular contest logging software, and I’ll use it for the examples in this article. The simpler software from N3FJP is also popular with beginners and has many of the same features.)

Get ready by reading the contest rules, have a world prefix map handy, lay in some snacks, and clear the weekend calendar for a few hours to get some CW exercise!

Programming Your Keyer or Software

Whether you are using manual or automated sending, there are only a few things you will need to send most of the time. Have them programmed into dedicated buttons or F-keys on your PC keyboard to send once:

- Your call (you rarely have to send a CQing station’s call)

- The exchange: 5NN followed by your section abbreviation or power

- Various contest “prosigns”: R, TU (for thank you), repeats of your section or power, and “?” or AGN for when you didn’t copy the other station’s information

- One key programmed with QRS at the highest speed you can copy so you can ask the other station to slow down into your range

My CW messages in N1MM+ are:

F1 – CQ

F2 – Exchange

F3 – TU and my call

F4 – My call

F5 – Their call (whatever is entered into the logging software’s call sign logging window)

F6, F7, F8 – Various exchange elements that I have to send such as serial number, QTH, power, etc.

F9 – AGN or “?”

F10 and other keys are spares. For ARRL DX, I have F6 programmed to send my section abbreviation a bit slower. I’ll use NØAX elsewhere in this article as “my call.”

Here’s a tip: I keep these messages in the same order for every contest so I don’t have to relearn which key is which. Also, F1 is dedicated to CQ messages by most contest logging software. Remember that N1MM+ has separate sets of messages if you are running (CQing) or search-and-pouncing (S&P). Program both sets and save your messages for use again next time.

Know how to quickly adjust your sending speed. This is usually a dedicated key on logging software—it is PageUp and PageDown for N1MM+, for example.

Above are two simple keyers: the standalone XT-4 Memory Keyer and the USB-connected K1EL WinKeyer. These have several stored messages sent by pressing a button, and a knob to adjust keyer speed. The WinKeyer’s USB data and message interface is also supported by a number of logging software packages.

Yet another tip: Do NOT add ANY extra information to your call sign, especially “/QRP”! You only want to send what the other station needs to get contact credit with your station. Send ONLY what you are legally required to send by your licensing rules and by the contest rules.

Be Ready

CW speeds from the DX station will be at least 25 to 28 WPM and often higher. If you are copying code at this speed, you are ready to jump into the pileups! Jump to the “Getting Through…” paragraphs. If not, that doesn’t mean your comfortable code speed needs to be that high. You can get the information you need for their exchange just by listening to the station through several QSOs since it doesn’t change in the ARRL DX contests.

What you will need to work on is recognizing your call sign at higher speeds. You can obviously practice this just by programming your keyer to send your call over and over. Turn down the volume to practice for weaker signals. Turn on your receiver so that you get some practice copying with some noise present or with other signals audible. When you answer a CQ, the responding station will send your call sign first, so be ready to respond when you hear your call sign. You should already have their exchange copied before you call, so all you have to do is press the key programmed to send your exchange back to them.

Cut Numbers

The sending station will probably use cut numbers to save time. Instead of “NØAX 599 100,” expect to hear “NØAX 5NN ATT.” You may already be familiar with NN as a substitute for 99, so 5NN is really 599. The A is an abbreviation for 1 (just the first di-dah) and the T is for 0. Another common substitution is K or KW for 1000. You can log either the translated number (9) or the cut number (N) and the log checker will know what to do with it. Listen first and figure it out before you call.

Section Abbreviations

US and Canadian section abbreviations are another thing a DX station has to know to log the contact correctly. These are all listed here on the ARRL website. The list is up to date with the new Canadian sections like “Golden Horseshoe – GH” in the Toronto area. Note that there are quite a few US abbreviations that start with M: MA, MD, ME, MI, MN, etc. This can be very confusing—copy exactly what the station sends and don’t make substitutions. For example, logging Missouri (MO) as MI or MS will show up as a “busted” contact.

Finally, remember that Hawaii (KH6), Alaska (KL7), Puerto Rico (KP4), and the US Virgin Islands (KP2) count as DX stations in this contest along with other US possessions like KH2, KH8, KHØ, and so forth. You’ll be able to tell from all the W and VE stations calling them! But W and VE stations don’t get contact or multiplier credit for working other W and VE stations. Only call stations for which you’ll get contest credit; otherwise, you’re just wasting their time. Remember that they will be sending their power and not an abbreviation for section.

Getting Through—Time and Frequency

Okay, you’re ready and prepared to call and respond. But how do you actually get through? There can be so many stations calling! The key is to sound different to the CQing operator so your signal stands out. You can do that by sending on a different frequency than the other stations or at a different time.

Let’s talk about timing first. My advice is “listen, listen, listen.” If only one or two stations are responding to the CQs or QRZ (sometimes the CQer will acknowledge an exchange with just R or TU and their call), be ready to hit the Send My Call key or button and immediately after the CQer stops sending. Immediately! Do not send their call or send your call more than once.

Be prepared to listen for your call or some fraction of your call (for example, “NØ?” or “AX?”). If you do, just send your call again, once. If the station responds but has your call wrong, such as “N9AX,” just send your call again, once. They will make the correction and then send your call and the exchange.

If more than one caller is responding, you might want to send a little slower than the other callers or delay by a second before sending your call. Or both! That means your call is going to be received after the other faster stations stop calling. This is particularly helpful if you have a small station. The idea is for your call to be “in the clear” when nobody else is sending. It’s likely that only part of your call will get through, so be prepared to correct or fill in your call as above.

What if there are lots of callers? A lot of them will probably have tuned to the CQer’s frequency by clicking on a spot from an online spotting network or cluster site (a.k.a. – via the TELNET window in N1MM+). Spots your software receives should be displayed in a band map or call list window. If you click on the call sign, your radio will be retuned to exactly that frequency. So far, so good, but every other station clicking on the call will also be exactly on that frequency. The result is a blur of many signals, all zero-beat with each other, and very difficult to sort out on the receiving end.

To stand out from a crowd, transmit on a slightly different frequency, offset by 100-150 Hz. You do this by turning on your radio’s transmit incremental tuning (also abbreviated XIT, ∆TX, and Clarifier) and experimenting. Try to place your signal at the same pitch as signals that are being answered. Or maybe to one side of the pileup—anything to stand out. This is not the same as operating “split” with two VFOs. Contest pileups rarely extend beyond 200 Hz either side of center. Any wider and you may be outside the receiving filter! Don’t forget to re-zero or clear your offset between QSOs. Some software, such as N1MM+, can do these automatically, including adding a small random offset to the spot frequency.

Finally, in a really big pileup (for example, a loud Caribbean station on Sunday after the bands have closed to Europe) you may have to pull out all of these tricks. Don’t be a “constant caller.” That only aggravates everybody, including the CQing station. Call once, maybe twice, then listen. If a contact hasn’t begun, call again but only once, listen again, etc. If you are a small station, it might be a good idea to tune away and look for another station. Often, there are stations available with hardly any pileup you can work easily. And after a while, the original big pileup may be gone!

The Contest Exchange

Assuming you’ve gotten through, heard your call come back, and a contest exchange, it’s YOUR turn! You’ve already gotten your exchange programmed into the keyer or logging software, so send it. Remember, only send it once, even if you are low power or QRP. There is no need to repeat anything unless you are asked for it. After all, you made it through, so you are being heard.

One press of the exchange key or button and you’re done, right? Well, maybe. What if the CQing station doesn’t receive it because of QRM or fading, or whatever? Be ready to hear TU or R. If you don’t, this is what could come back:

NØAX? — They didn’t hear anything, so send your call once and the exchange. In N1MM+, that’s F4 followed by F2 if your F-keys are arranged like mine.

AGN or AGN? or just “?” — Send the exchange again, once using F2.

STATE? or SEC? — Send your state or section abbreviation again once or twice. If you are really having trouble getting it through, drop your speed two or more WPM and send it again. Same general idea if you are a DX station working a US/Canada station and hear “PWR?”. Slow down and send it once or twice.

And if they didn’t get your call right, just send your call again once. They should correct the call in their software and send it with the exchange again.

Continuous Improvement

Wow…that was fun, wasn’t it? Now do it some more! It will get easier and easier with each QSO. The hours will fly by, and your log will fill with call signs and locations from all over. Don’t forget to send in your log as explained in the rules. It helps the sponsors with log-checking and gives them a more accurate idea of who and how many are participating. And you might even get a certificate if you’re lucky! If you are a Logbook of The World user, upload your logs to that service as well.

There are lots of opportunities through the year to get on the air and operate. Be sure to encourage others in your club or group to take the plunge. Offer to host and mentor them at your station or maybe you’ll be invited to operate with another group. Field Day teams are always looking for CW operators. I guarantee that your code speed will improve, too. And that is really the whole point of contests—a good workout that improves your station and your skills.

Appendix: Basics for CW Contest Success

Let’s start with some realistic expectations. If you haven’t operated CW very much, a big contest like ARRL DX is not the way to get started. You’ll be frustrated and won’t have a good time. It’s best to practice CW until you are comfortable at 15 WPM or higher. I also suggest that you participate in some less-hectic contests, like State QSO Parties or the weekly Slow-Speed Test (SST) run by the K1USN club. These will also acquaint you with the general flow of CW contests.

If you find yourself intimidated by the contest, it’s perfectly fine to just listen for practice. Contests are great ways to increase your copying code speed! The contest exchange is the same for each station throughout the contest: signal report (everybody sends 5NN) and either a two-letter section abbreviation or numeric power. You can tune in a strong station “running” a pileup and just listen to them work other stations. Here’s a tip: Code speed and the rate of working stations drops somewhat on Sunday. You might find it easier to copy on the contest’s second day.

You also need to use a keyer and paddle or a computer with a keying interface…or both. A straight key will be too slow and trying to keep up will wear out your arm in short order! Make sure you can key the radio properly and that the paddle is correctly adjusted.

What about using a code reader? I don’t recommend this because code reader software doesn’t handle the pileup environment very well. (CW Skimmer by Afreet Software is an excellent decoder, but it isn’t a general-purpose code reader.) The reader may pick out call signs but anything else is probably questionable. You are better off training your ears.

It’s often easier for beginners to record the call sign and exchange on paper, then type it in to your logging software at a leisurely pace. Logging software is also highly recommended if you plan on submitting a log. You can also create the necessary Cabrillo format file by using an online manual entry converter if you prefer. Nevertheless, it’s a lot easier to get some contest logging software that generates the Cabrillo format automatically. Most general-purpose logging software can generate ADIF files that you can then convert to Cabrillo with a utility program. (Search for “adif cabrillo converter” to find several options.)