Most Hams associate the term “DX” with the HF bands. It’s understandable. After all, as conventional wisdom states, the HF bands allow international, global communication, while the VHF bands are for local or regional contacts. But there are plenty of ways that DX can be worked above 50 MHz.

What is “DX” anyway?

The term “DX” is an abbreviation for “Distance X” or “Distant Transmitter.” It generally means hearing or making contact with faraway stations. DXing takes several forms. Shortwave Listeners (SWLs), Broadcast Band (BCB) listeners, FM aficionados, and Non-Directional Beacon (NDB) monitors all use the term “DXing” to talk about their hobby. And in each of those fields, the definition of DX is different.

The average Ham probably wouldn’t consider a QSO from Arizona to Ontario to be DXing, but such a QSO on 432 MHz or the microwave bands might be. So the definition of “DXing” can change, depending on what frequency you’re using.

My recent blog on VHF propagation modes explains how interesting natural phenomena can allow signals on 6 and 2 meters to travel far beyond line-of-sight distances. These modes open the door for DX contacts of all varieties to be made on those bands.

But let’s suspend the philosophical discussion of how the definition of DX fluctuates based on what frequency you’re operating on, and get right to the point: Many people work different countries on the VHF+ bands, and YOU can, too. The ARRL offers DX Century Club (DXCC) awards on all the VHF bands; several hundred have completed DXCC on 6 meters; 9 have DXCC on 432 MHz; and a couple Hams have worked multiple DXCC entities as high up as 24 GHz!

In many cases, substantial equipment will be needed to complete DX QSOs on higher frequencies, but not always. Let’s take a look at the major ways international QSOs can be made on the VHF+ bands.

F2 Propagation

During exceptionally good peaks of the 11-year solar cycle, the Maximum Usable Frequency (MUF) can exceed 50 MHz, and the F2 layer of the ionosphere will allow long-haul QSOs to occur. This is simply an extension of the same propagation mode that allows DX to be worked on HF.

Multi-Hop Sporadic-E on 6 meters

Sporadic-E occurs when ionized clouds of gas form in the E-layer of the atmosphere. When they become dense enough, they can reflect radio signals and allow them to cover distances of several hundred miles per “hop.” On occasion, several clouds align themselves in differ parts on the ionosphere, creating multi-hop paths. In some cases, these clouds align themselves across oceans, creating multi-hop openings to Europe and Central/South America, and even west Africa, Asia and Oceania. While multi-hop sporadic-E propagation can occur at any time, it seems to peak around mid-June to mid-July. New England stations statistically see the most multi-hop openings to Europe, and the West Coast of the U.S. sees the fewest. These multi-hop openings can be very short, just a few minutes or less in some cases. Midwest operators can see openings into Europe, South America, and occasionally Japan. The West Coast sees multi-hop openings to Hawaii and Asia/Oceania. However, it must be stated again that these openings require several clouds to form simultaneously, and in the proper alignment, to facilitate long-haul contacts.

EME (Earth-Moon-Earth, or Moonbounce)

Some Hams enjoy using the moon as a passive reflector, sending their VHF+ signals into space, where they bounce off the surface of the moon and back down to the earth. QSOs are possible between any two areas of the Earth that both have the moon above their horizon. All bands above 50 MHz can be used, but some bands are easier (and more popular) than others.

EME is not for the timid. Under the most optimum of conditions, more than 90% of a transmitted signal will be lost over the nearly 760,000 kilometer path. Radio signals traveling at the speed of light take 2.7 seconds to make the trip to the moon and back. The most successful EME stations are accomplishments of engineering, with multiple phased antennas, lots of power, and low-noise preamps that boost the received signal without increasing the noise. However, that is not to say that making EME contacts with smaller stations is impossible. Many EME contacts have been made by Hams using 100 watts and single, long-boom Yagis. To be certain, these smaller stations generally work other big gun EME stations, with the big guns doing most of the heavy lifting to complete the QSO. The advent of digital mode software by Nobel Prize winner Joe Taylor, K1JT, has made reception of weak signal transmissions several dB below the noise floor possible, and has been a boon to EME activity, as well as terrestrial propagation modes. While technically challenging, EME is not as difficult as it once was, and can be achieved by Hams with modest stations who are willing to do their homework.

Satellites

Careening overhead at around 17,000 miles per hour, the transceivers aboard satellites allow VHF/UHF communications over thousands of miles. There are numerous satellites in orbit that use FM, SSB/CW, and digital modes. Today’s satellites are Low-Earth Orbit (LEO) satellites, meaning they are only above your horizon for no more than 15-20 minutes at a time. Nevertheless, true DX contacts can be made on the “birds” with a little effort.

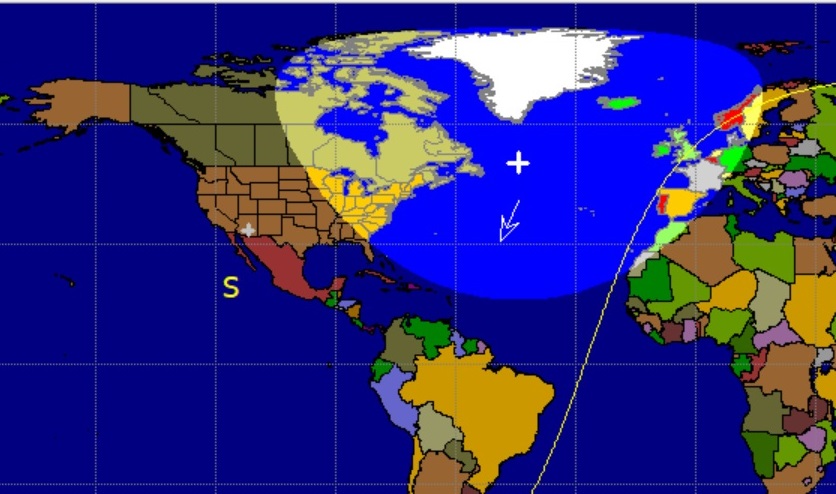

As a satellite moves overhead, the locations where a satellite comes up over the horizon and simultaneously disappears below the horizon are constantly changing. The area a satellite covers at any given point in time is called a footprint. Anybody within the footprint of a satellite has the opportunity to make contacts with other stations also inside the footprint. The size of a footprint is dependent upon how high the satellite is above the earth. This will vary from satellite to satellite.

Satellite passes that cover areas of the United States and other DXCC entities at the same time are relatively common. Opportunities exist regularly for all parts of the U.S. and Canada to make satellite DX QSOs into Central America and the Caribbean. Stations in New England and the Midwest have frequent opportunities to make DX QSOs with stations in western Europe.

While making DX QSOs on even the FM satellites can be accomplished with a little effort, real DX is possible on the most venerable of satellites, Oscar 7. Launched in 1974, it remains operational today, but is extremely fragile. It has the largest footprint of any of the LEO satellites in orbit today. QSOs of just over 8,000 km have been accomplished on Oscar 7. I’ve successfully worked Spain from Wyoming on Oscar 7, a distance of about 7,400 km. Another popular satellite, FO-29, has a footprint of around 7,500 km. FO-29 offered regular openings into Europe from my former location in Connecticut.

If you’re fortunate enough to live on the East Coast, DXCC is mathematically possible on satellite using only today’s LEO satellites. However, there has to be a Ham active in satellite operating in all of those countries, which is not always the case. Many DXCC entities in the Caribbean that are common on HF are quite rare on satellite, simply due to no satellite operators in those countries. HF operators who take vacations to the Caribbean, take note! A simple satellite station doesn’t take up much space, and you could be quite popular!

Equipment Needed

Working DX on the VHF+ bands can be a significant technical and operational challenge. However, that’s not the case in many circumstances.

Satellites: DX QSOs can be made on the FM satellites using a dual-band HT and a handheld dual-band Yagi, such as the Arrow or Elk antennas. For the SSB/CW satellites, a satellite-capable transceiver, or two all-mode radios capable of operation on 2 meters and 70 centimeters, along with dual-band antennas, can successfully make DX QSOs. You don’t even need much power; the vast majority of satellites can be accessed with only five watts. To take your first steps in FM satellite operating, see my previous blogs, Satellite Basics Part 1 and Satellite Basics Part 2, for step-by-step instructions.

EME: With 90% signal loss under even the best of EME circumstances, there’s no doubt that big stations will have higher rates of success. However, the advent of K1JT’s suite of digital modes has made it possible for small-scale EME stations to enjoy some success. 144 and 432 MHz EME QSOs have been completed using 100 watts of power and single long-boom Yagis set up in a backyard.

Six Meter Multi-hop Sporadic-E/F2: The amount of gear needed is dependent entirely upon the intensity of the opening. If an opening is strong, you can work serious DX with a small station. I’ve worked plenty of multi-hop openings to Europe and South America on 6 meters from Connecticut using 100 watts from an Icom IC-706 and a 3-element Yagi on a pole 20 feet off the ground. During the solar peak in 2001, I worked New Zealand from Illinois on 6 meter SSB via F2 using 25 watts from an old Yaesu 625RD transceiver and a 3-element Yagi at 70 feet. However, larger stations will have access to the weaker or shorter-duration openings that smaller stations will not. Don’t let that stop you from trying, though! The advent of the FT8 digital mode has put working DX on 6 meters within the grasp of many a Ham with a modest station.

Conclusion

DXing on the VHF+ bands IS possible for hams who are willing to undertake the challenge of learning new skills and acquiring the extra gear needed. Some of these challenges are significant, but they are not insurmountable. I encourage all hams to expand your horizons to include these VHF operations in your activities. You will learn a lot in the process, and the satisfaction of completing a DX contact on VHF/UHF is addictive!

Further Reading

It is impossible for this blog to cover all of the intricacies involved in working DX using these modes and techniques. I recommend these sources for learning more about the activities I’ve mentioned here.

EME on a Budget: Moonbounce for the Rest of Us by Paul Bock, K4MSG

An Introduction to Moonbounce by John Lemay, G4ZTR

6 Meter DXing for Little Pistols by Edmun Richmond, W4YO