A look at the life of one priest’s push to keep his religion on the cutting edge of technology using amateur radio and his ultimate sacrifice during World War II.

***

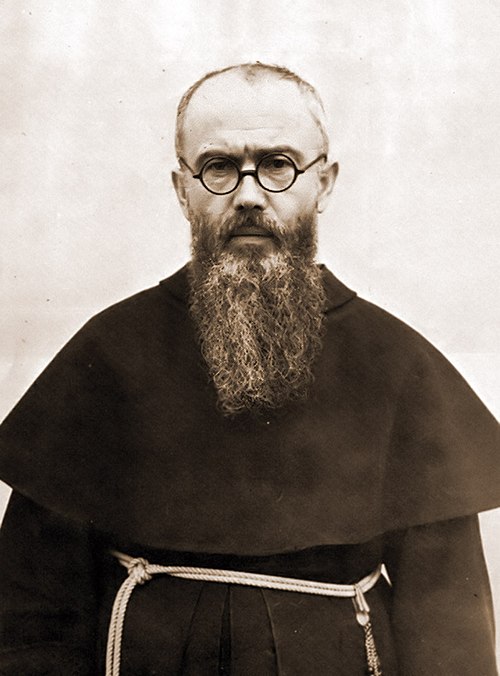

At first glance, the intersection of religion and something like amateur radio might not be immediately apparent. Look hard enough, though, and you’ll find stories like that of Maximilian Kolbe.

Born Raymund Kolbe in Poland, his life changed forever when he was struck with a vision of the Virgin Mary at 12 years old. Holding two crowns, one red and one white, she asked him if he was willing to accept either.

“The white one meant that I should preserve in purity,” Kolbe said, according to Catholic.org. “And the red, that I should become a martyr. I said I would accept them both.”

A year later, Kolbe joined the Conventual Franciscans with his brother in 1910. He would later be given the religious name Maximilian. By 1918, he was an ordained priest with the primary goal of promoting Mary throughout Poland.

During this time, he helped set up monasteries in Japan and India. It was in Japan where the priest got introduced to a small network of broadcast radios and realized the potential behind them. Interested in using the most modern technology to help spread his message, the gears began working on how he may be able to use radio to aid his efforts.

Later, he returned to manage Niepokalanów, then the largest Catholic monastery in the world, which he helped found in 1927. At its height, it housed 760 men and published millions of books through its on-campus publishing house. It was here that Kolbe truly began looking into amateur radio to spread the Virgin Mary’s word.

In 1938, he started a radio station “Radio Niepokalanów,”which held the call signSP3RN (SP is the prefix for Polish radio stations). Even before it was launched, the license was tricky to get due to restrictions and limitations on who could use the airwaves in Poland at the time. Once they got the license, the monks built the station on their own using anything they could get, including things like early vacuum tube condenser microphones, according to SaintMaxNet.org. They began delivering sermons over the radio shortly after.

When the war began, Kolbe and a few other monks continued operations at the monastery, leading to the formation of a temporary hospital. In 1939, he was arrested and released months later. During that time, he was given an opportunity to sign a document called the Deutsche Volksliste, which would have recognized his German roots and given him rights like other German citizens. He refused.

Kolbe continued to run the station and publishing house, where he produced religious works and other pieces that were widely considered anti-Nazi, according to multiple reports. More importantly, he gave refuge to those impacted by the war and the crimes against humanity that the Nazis committed. This included protecting around 2,000 Jewish people.

German officials later closed the monastery on February 17, 1941, and arrested Kolbe and four other men, eventually taking them to Auschwitz. There, Kolbe continued to act as a priest, giving sermons while enduring the horrors that happened at the camp.

On July 29, 1941, following a prisoner escape from the camp, Nazi officers chose ten men to serve as an example to prevent further attempts. They would die by starvation in an underground bunker. Kolbe volunteered to take the place of one of the men—a prisoner who would leave a family behind upon his death.

Records and eyewitness accounts say that Kolbe led the men in prayer and each time the guards checked on him, he was always standing or kneeling in the center of the room.

After three weeks, following intense starvation and dehydration, only three men and Kolbe were alive. Needing the bunker for space, the guards opted to give them lethal injections. When it was his turn, it’s believed that he raised his left arm and calmly waited for the injection. The next day, his body was cremated.

Following his death and the end of the war, Kolbe’s contribution to the Catholic faith was long debated on whether he should be canonized into sainthood or not. Originally, he was not considered because his death was not technically due to odium fidei, or hatred of the faith. So, at first, he was named a confessor and martyr of the religion.

However, on October 10, 1982, Pope John Paul II overruled this decision with the reasoning that what the Nazis did was a hatred to all humanity, including Christians. He was canonized as the patron saint of drug addicts, prisoners, families, and the pro-life movement, according to Catholic.org.

While the Catholic Church doesn’t officially recognize it, his efforts broadcasting his sermons to the masses using this method has cemented him as the “Patron Saint of Ham Radio.”

There are a lot of reasons to appreciate the life and struggles of Maximilian Kolbe. He is honored by many for his religious outreach and sacrifice during the war, protecting and healing those impacted, being a voice of dissent against war crimes, and for his eventual fate in Auschwitz while saving another man condemned to die by starvation.

Hams should honor him for his use of amateur radio to spread his messages of the Virgin Mary and his opposition to the Nazi war machine. His interest in finding new ways to spread his sermons led to one of the few radio licenses given to an entity at a time in Poland where strict guidelines made it near impossible to get them. He even helped build the radio station he used with the tools and equipment they had on hand.

He embodied that true ham spirit of “where there’s a will, there’s a way.”

By the way: the man he rescued from death by starvation? His name was Franciszek Gajowniczek. He passed away in 1995—at the age of 94.