Who or what is Q? In James Bond films and novels, he was the head of Q Branch, which developed all the cool gadgets that Bond used in his missions.

Remember the laser Rolex, Dentonite toothpaste explosive, and “Little Nellie,” a compact helicopter equipped with heat-seeking missiles? All these solutions helped keep 007 alive while fighting the evil organization, Spectre.

Radio also has a Q: Q-codes.

What Are Q-Codes?

Q-Codes are a valuable solution to a very practical problem—how to convey frequent, routine messages quickly and unambiguously across language barriers using Morse code. Imagine you’re a ship radio op in 1909: storms outside, static inside, and someone asks for your position in a language you don’t speak.

Q is a quick solution.

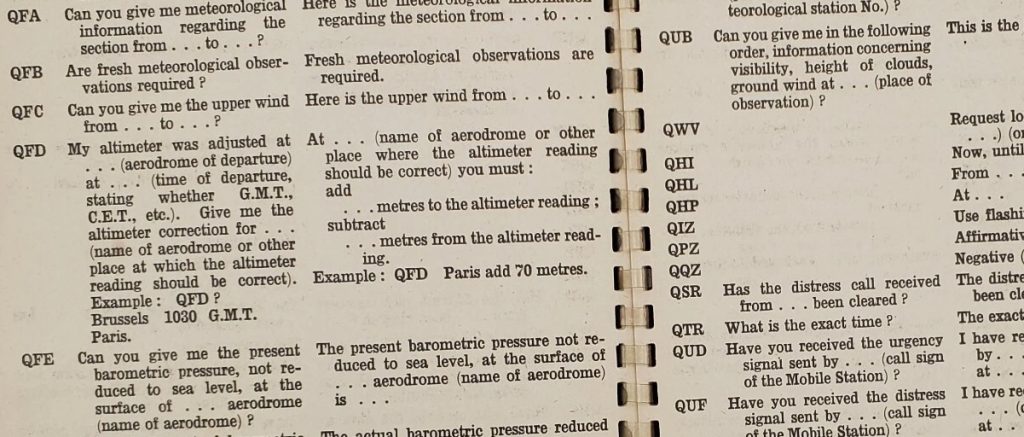

The British General Post Office (GPO), in cooperation with the Admiralty and the Board of Trade, drew up the initial list of Q-codes around 1909 for use by British ships and coastal stations. The list covered frequent operational queries and reports—signal strength, interference, location, course, weather, and administrative confirmations. These Q-codes became three-letter abbreviations, packed with meaning—no more long essays in dits and dahs.

Why Q? Partly because Q doesn’t start many ordinary words across European languages. It also has a distinctive Morse pattern (– – · –), which helps when the airwaves sound like frying bacon. Best of all, when operators heard a Q, they knew a standardized, useful bit of information was coming.

Sentences like “Please be so kind as to advise your current latitude and longitude, old chap” became QTH?—a savings of words, watts, and patience. Q-codes were immediately useful in congested airwaves where rapid, routine exchanges kept traffic flowing.

The true genius was the dual personality. Send QTH? and you’re asking, “What’s your location?” Send QTH London, and you’re declaring “My location is London.” One code, two moods. Compact, fast, and less error-prone, this economy of words made the system extremely flexible.

Boats & Planes

The sinking of the Titanic in 1912 focused global attention on radio procedures, distress signaling, and inter-operator clarity. At the International Radiotelegraph Conference in London that year, the already-useful British Q- codes were introduced on the world stage.

Over the following years, and especially at the 1927 Washington conference, the burgeoning International Telecommunication Union helped standardize the lists. The result: ships, coast stations, and later, a diverse collection of services all spoke Q with the same accent.

You could cross oceans without crossing wires.

Aviation soon joined in. Pilots and controllers were wrestling with airplanes and radios at once; long sentences were not practical in the cockpit. So a specialized set of Q-codes landed: QNH (set your altimeter to mean sea level pressure), QFE (pressure at field elevation), QNE (standard pressure), QDM (magnetic bearing to the station), QDR (bearing from the station).

These are the radio equivalent of cockpit sticky notes: short, crucial, and unlikely to be confused.

As aviation expanded, Q-codes found a new home in the skies. Pilots and ground controllers needed brief, precise communication, especially during navigation and landing operations. International flights increased the importance of standardized communication methods, and Q-codes provided a reliable solution.

Q-codes are still used today—a reminder that even cutting-edge technology sometimes sticks with old habits that work.

Adoption by Amateur Radio

Meanwhile, amateur radio operators discovered Q-codes and immediately adopted them the way teenagers adopt slang. Hams used them in Morse, then in voice, then everywhere. QTH? instead of “Where are you?”; QSO for “conversation”; QSL for “acknowledged” (and later for the postcard you mail to prove you actually talked to Hong Kong); QRP for low power; and QRO for high power. For operators communicating across continents using Morse code, Q-codes were a dream come true. They allowed users to quickly and efficiently share signal reports, locations, and operating conditions.

Over time, Q-codes became part of amateur radio culture. Many amateurs even use them in casual conversation, confusing outsiders who may wonder why someone is talking about QRM instead of just saying, “There’s a lot of noise.”

Other staples include QST (message to all radio amateurs); QRN (atmospheric noise); QSB (fading); QSY (change frequency); QRZ (who is calling me?); and QRT (stop transmitting).

Other Services

The Q system also coexisted with other frameworks. Military and some commercial services developed Z codes, and aviation adopted a parallel phonetic alphabet and plain-language procedures for voice communications. Yet Q-codes remained valuable wherever Morse endured, and even in voice—where brevity and tradition mattered.

Their resilience stems from the way they compress meaning without ambiguity. For example, QRM 5 instantly conveys “Severe interference,” with a standardized report scale, saving time and avoiding uncertain language translation.

Over the 20th century, the official ITU list evolved. Some Q-codes were quietly retired from regular use, while others—especially those tied to safety, navigation, and everyday operating practice—earned a permanent place.

The Q-code’s design philosophy endured: concise, information-dense, and service-neutral whenever possible.

Radiotelegraphy in most services, such as maritime safety, aeronautical operations, and amateur radio, held onto the core sets that continued to meet their operational needs—proving that when something works under stress, bad weather, and occasional human confusion, it tends to stick around.

Q-Code Assignments

- The QAA…QNZ series are reserved for the aeronautical service

- The QOA…QQZ series is reserved for maritime services

- The QRA…QUZ series is for use by all services, including amateur radio

- The QZA…QZZ series for other uses/services

Take 10

You can’t talk about Q-codes without mentioning their not-so-distant cousin, 10-codes. They are related as similar tools for concise communication. But Q-codes are universal and rooted in telegraphy, whereas 10-codes are a more modern system and agency-specific. Q-codes and 10-codes serve the same purpose of shortening and clarifying radio communication, but they came from very different technological and cultural ecosystems.

Ten-codes were introduced in the United States in 1937 by APCO (Association of Public-Safety Communications Officials) for voice radio, primarily for law enforcement and public safety. They were designed for spoken clarity rather than global harmony.

In the early days of police radio, it was common for a police department to have only one shared channel, making 10-codes important. Much like the Q-codes, they kept transmissions short and provided simple, effective communication. While neatly numeric, 10-code meanings have sometimes varied by agency or region. Occasionally, this would turn standardized communication into a real-time guessing game during multi-agency communications.

Ten-codes worked their way into popular culture by CB radio enthusiasts. C. W. McCall’s hit song “Convoy”(1975), featuring conversations among CB-communicating truckers, popularized phrases like “What’s your twenty?” (10-20) in American English. And who could forget Broderick Crawford in “Highway Patrol,”barking 10-4 into his mobile radio. Ten-codes have gradually yielded to plain language, proving that fame and operational reliability are not always the same thing.

Q—Still in the Queue

Culturally, Q-codes built a shared radio identity. They’re the secret handshake that isn’t so secret; you hear a QTH or a QSY and immediately know you’re among radio people. You don’t just say “Change frequency?” You say, “QSY?” Everyone nods in the same language.

In some parts of the spectrum, they’re still the best tool for the job. It gets through even when the band is barely open. When noise conditions are rough, a crisp QRN does the job better than a paragraph. If you want to confirm a contact, QSL? is as clear as a stamped postcard or QRZ posting.

Are you done for the night? QRT lands with the authority of an off switch.