If you’ve spun the dial on your HF transceiver lately and found nothing but static, you’re not alone. For many operators, the once-bustling shortwave spectrum sounds more like the emptiness of deep space than a lively ham community. But are the HF bands really dead—especially when we’re close to the solar maximum for Cycle 25—or is something else at play? Let’s explore why HF bands feel quieter than they used to, and what factors have combined to create this impression.

Here Comes the Sun

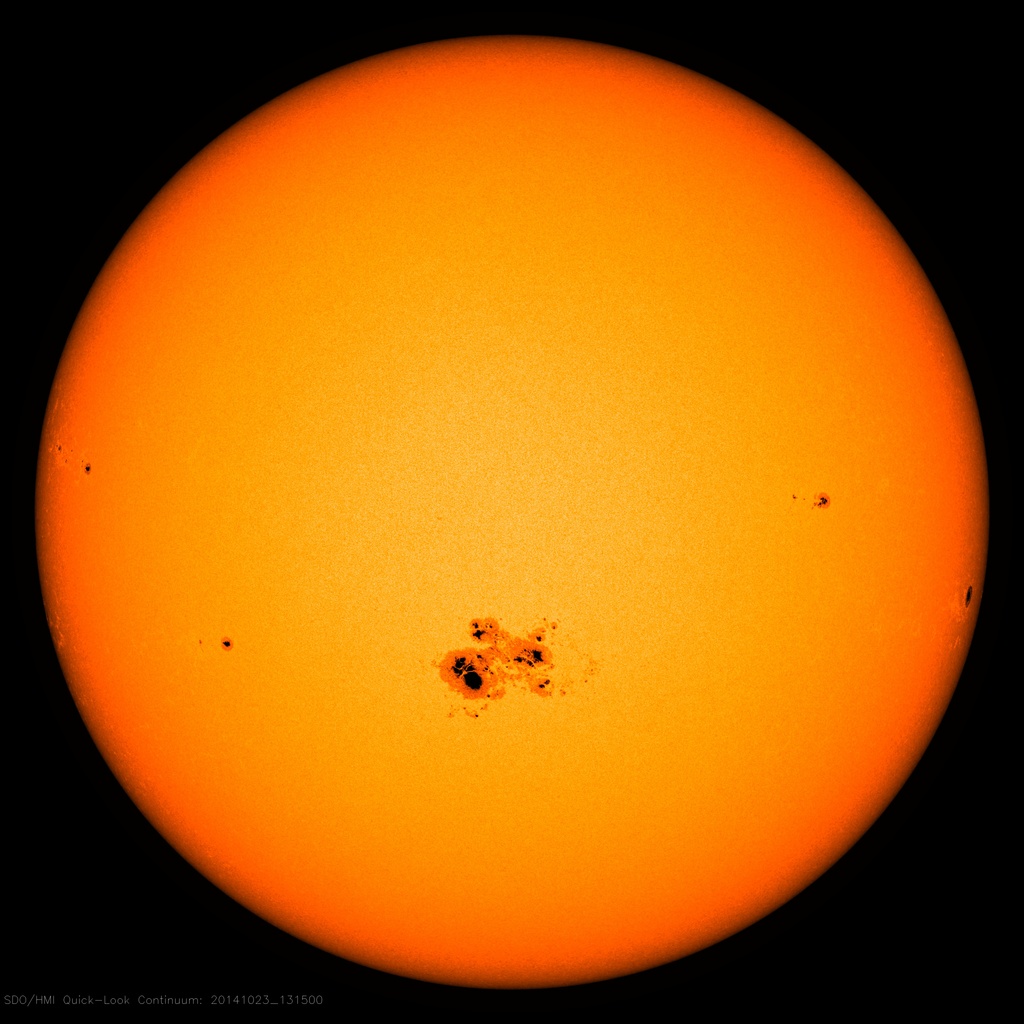

When the sun gives us sunspots, it ionizes the upper atmosphere and turns 10 meters into a nonstop DX highway. But when the sunspot cycle bottoms out, the ionosphere stops bending HF signals and starts acting more like a stubborn brick wall.

Higher solar activity generally improves long-distance communication on the higher HF bands (10M, 12M, etc.) because a more ionized F-layer reflects higher frequencies more effectively. However, solar flares and geomagnetic storms, which have become more frequent during the maximum, pose a greater risk of severe absorption and blackouts.

- Factor 1: HF isn’t really gone—propagation is never consistent, even during solar peaks.

Death by Static

Once upon a time, hams feared lightning and power lines. Today, HF operators are plagued by the noise of LED light bulbs, plasma TVs, phone chargers, Wi-Fi routers, and solar panel inverters, all of which generate RFI across the entire spectrum.

You may think the bands are empty, but really, there’s a rare station on 20 meters calling CQ right now. You can’t hear him because your neighbor’s solar panels are blasting RF hash into your shack at S9+.

- Factor 2: HF didn’t die —it got buried alive under a mountain of artificial noise.

Off the Reservation

Where did all the hams go? In the old days, 20 meters sounded like a crowded party. Today, it’s like showing up late to a party and realizing everyone has already left.

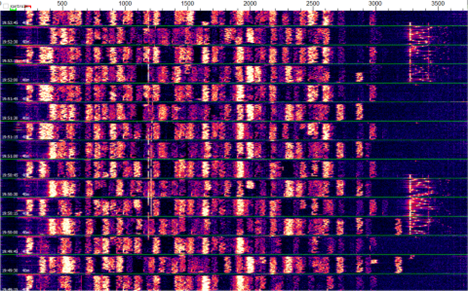

- Factor 3: The truth is, hams didn’t leave HF — they just migrated to digital modes. Thousands are currently on FT8, exchanging short bursts of data. On a waterfall display, it looks like Los Angeles at rush hour. But to your ears, it’s just a faint beep-beep in the background. You tune across the dial and think: “The bands are dead.” Nope. Everyone’s just talking in 1’s and 0’s.

The Internet Rules

Let’s face it. The magic of hearing a voice from across the ocean seems less impressive when you can FaceTime a guy in Australia while ordering pizza on the same screen.

HF once offered something miraculous: instant global communication. But you tell some tech-savvy kids about how you spent three hours trying to contact Latvia on 20 meters and they’ll think you’re from the Stone Age.

DMR, D-STAR, System Fusion, and a host of new digital voice modes offer new possibilities. With the aid of an MMDVM hotspot, OpenSpot, or a similar device, hams can communicate with the world using an HT via a Wi-Fi connection. Recent developments have even rendered the radio obsolete. You can actually use a single box that will emulate many of the digital voice modes, minus the RF.

- Factor 4: HF’s charm hasn’t died, but it’s competing with today’s high tech.

It’s Only Resting

HF isn’t truly dead. During contests, the bands can come alive. On a good day in Solar Cycle 25, 10 meters can sound like a hamfest gathering. And if you actually call CQ instead of just listening, you might be surprised how many stations come out of the woodwork.

The silence is an illusion. Sometimes the band is open, but nobody’s transmitting because they think it’s closed. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy: “I don’t hear anything, so I won’t transmit, which means nobody hears me.”

And the HF silence continues . . .

Perception vs. Reality

Here’s the paradox: HF is not truly dead. In fact, during contests, Field Day, or DXpeditions, the bands can be wall-to-wall with signals. Thousands of operators still use HF daily, particularly on 20 and 40 meters. Nets still meet at their appointed time. The difference is that the casual background chatter that once filled the spectrum has thinned out.

What’s more, propagation conditions can fool us. HF signals fade in and out with ionospheric changes. Just because you don’t hear activity in your location doesn’t mean the band is empty worldwide. A quick check of DX clusters or reverse beacons often reveals a lively band that doesn’t reach your corner of the Earth at that moment.

Dead or Alive?

So, are the HF bands really dead? They’re resting, having a nap while the Sun moves through its 11-year cycle. What you’re hearing—or not hearing—is a mix of bad solar weather, noisy consumer electronics, and hams who traded their microphones and Morse keys for soundcards.

When solar cycles awaken, HF comes back to life. Ten meters, once a barren wasteland, opens like a drive-thru window at dinnertime. Even weather events can trigger long-distance contacts on VHF and higher bands. Like an RF waveguide, tropospheric ducting channels carry RF signals potentially hundreds of miles when a temperature inversion occurs naturally, typically over large bodies of water or wide-open spaces.

If you want the bands to feel alive again, don’t just listen—transmit. Call CQ. Fire up digital modes. Try at night, try at dawn, try during a contest. And remember: The best way to resurrect HF is to use it.

Twin Peaks? The NOAA and NASA predict a second peak between now and March 2026.