I mentioned previously the concept of writing a contest “post-mortem.” The idea is to write down what went well and what went poorly, and to do so soon after the contest is over. A good way to capture ideas during the heat of battle is to use the notepad feature built into many contest logging programs. Most contest loggers allow you to enter a one-line note for the current QSO. You can also just jot down notes on a scratch pad for later review.

One advantage of using the software’s note feature is that the note is time stamped and assigned to a particular QSO. The time stamp feature can be helpful for identifying the exact time a band opening occurred, for example. There is another source of helpful data for post-contest analysis, but we have to wait until the results are published to get it. We are talking about the log checking report.

Understanding Your Log Checking Reports

One of the benefits of computerized log checking is the ability to cross-check QSO information between submitted logs. Each submitted log contributes to the cross-check database and increases the log checking accuracy for everybody. This is one of the reasons that it is always important to submit your log for every contest effort, no matter how small. Another good reason is that you might win some wallpaper. You’ve got to enter to win. The log checking report may go by different names, including LCR, UBN (Unique, Busted, Not-In-Log) or other names, depending on the contest sponsor’s choice.

Not every contest provides a log checking report, but many of the major contests provide some kind of accuracy feedback. Some contest sponsors require that you specifically ask for a report. Other sponsors automatically generate a report for each entrant and make that report available on a web page (usually behind a password.) There are even a few contests in which the logging accuracy of the participants is published as a part of the final results.

Regardless of the name or the method of access, the idea is the same; and that is to learn from our mistakes. One reason to care about studying log checking reports is to improve accuracy. Accuracy is paramount not just in contesting, but in all traffic handling. Some contests have penalties for errors. The CQWW, for example, removes not only the busted QSO, but an additional two QSOs’ worth of points are deducted as well. You can also lose multipliers through logging errors and the resulting score reductions that will result. Some contests have been won or lost by a few QSOs. Logging accuracy is often the determining factor in such close races.

Let’s look at an example. Here is my LCR from the 2009 CW November Sweepstakes, which I have edited for brevity.

(Log checking report from ARRL.org)

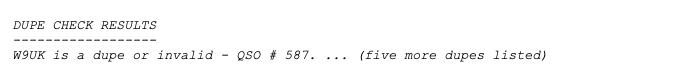

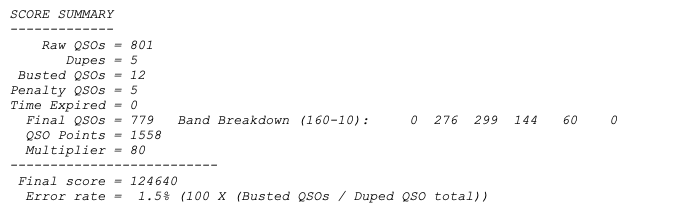

Note that dupes do NOT count against me. All dupes are treated with no penalties. This is one of the reasons that it is usually best to just log dupes and move on.

This is good. I only missed one minute of allowable operating time.

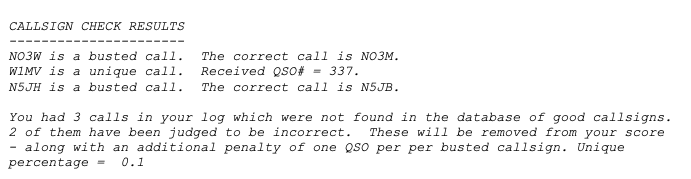

Okay, looks like I busted NO3M. I must have missed this as Ty blew by me at the likes of 50 WPM. I should have known better but missed it. It looks like I also have trouble with the letter “H” and turned it into a “B” instead. Note that I lost the equivalent of four QSOs here—two for the calls that I busted and two more for penalties. I “got away” with W1MV because it could not be judged a bad call sign. It was flagged because I was the only one to work W1MV. It was “Unique.”

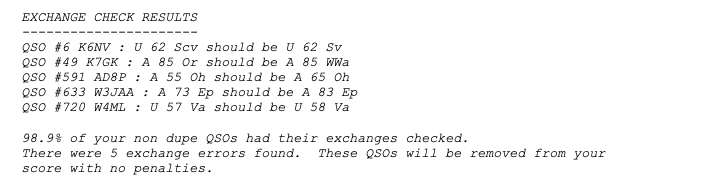

Ouch. I lost five more QSOs’ worth of points in this batch due to errors in the exchange information. I’ve got to be more careful with those California sections which sound similar. Not sure how I turned WWa into OR; they don’t even sound alike. My suspicion is that I must have been tired and logged what I thought I heard. That’s a nice way of saying that I probably guessed; and it cost me, as it should have. Note that almost 99% of the QSOs had the exchanges checked. There is a very high probability that any errors WILL be found.

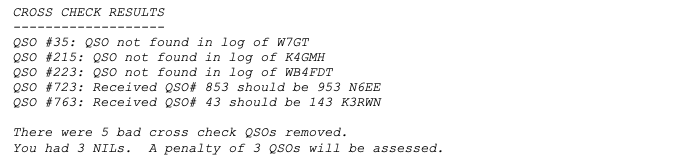

Oh no! More QSO points down the tube. Somehow my QSOs with W7GT, K4GMH, and WB4FDT did not wind up in their logs. I must have worked somebody else at the exact time, somehow thinking that they were working me.

Another possibility is a software glitch on their end of the QSO, resulting in my QSO not being logged.

Another possibility is that they simply gave up on my weak QRP signal, and I could not copy their “NIL” (Not-In-Log) reply. It’s important to send “NIL” if someone weak is not making it into your log. Notice that there was an additional QSO penalty assessed for each Not-In-Log call sign. I also busted two exchange numbers, turning 953 into 853 and 143 into 43. No penalty was assessed for these errors, but I did lose all of the points for those QSOs.

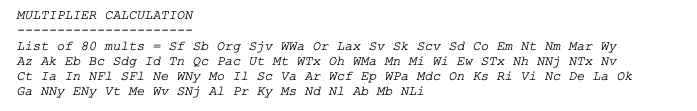

I worked all 80 sections and made a sweep! Thankfully, none of my busted QSOs were with a multiplier worked only once. I try to pay even extra attention to rare multiplier QSOs to make sure that I don’t get dinged.

The Score Summary section shows the final effect of the score cross-checking, with all of the busted QSOs and penalty points applied before calculating the final score. Of particular note is the Error Rate number—in this case 1.5%. The goal is to make this number as small as possible. The best way to reduce this number is to never guess and ask for a repeat if needed.

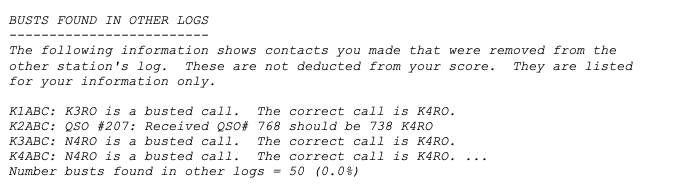

This last section shows mistakes made in the logs of the operators that you worked. (Note: The calls have been changed to protect the identity of the operators.) This section can be useful to identify recurring errors that others make trying to copy your information. For example, if you see certain letters getting busted over and over, you might want to try different phonetics. Perhaps you might try some subtle spacing changes on CW to separate troublesome characters.

If all else fails, there is always the vanity call sign system. 😀

That’s all for this installment. See you on the bands, and don’t forget to submit your log to the sponsor, no matter how many QSOs are in the log. It improves the log checking potential accuracy and will allow you to get a log checking report.