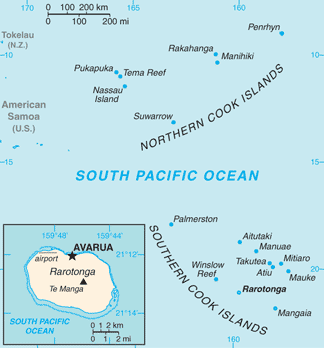

In October 2025, a small group of active DXpeditioners—Rob, N7QT; Robin, WA7CPA; Brian, N9ADG; Jack, N7JP; James, KC7EFP; and myself, Violetta, KN2P—made our way across the globe to activate #68 on the DXCC most wanted list, the Northern Cook Islands. The destination was Manihiki, a small atoll in the South Pacific which is home to 200 Māori, the indigenous Polynesian people of the Cook Islands. The 1.5-square-mile island is located over 800 miles from the main island of Rarotonga, making Manihiki one of the most remote inhabitations in the South Pacific.

The team traveled separately from the U.S. and met on the main island of Rarotonga, where the capital of Avarua is located. On Tuesday morning, October 7, we loaded our gear and baggage onto an Embraer 110 aircraft and took off for Manihiki. The total flight time was about three hours, including a short stop in Aitutaki to refuel. The only way to reach the atoll is on a flight operated by Air Rarotonga, the inter-island airline that runs both scheduled and charter flights. The service to Manihiki runs every other week on Tuesdays. Once we landed in Manihiki, there was no way to leave until the next flight two weeks later.

After landing on the 4,800-foot coral runway that ran along the shore of the atoll, we were greeted by the villagers with ‘ei—garlands of vibrant flowers—and fresh coconuts that were harvested that morning. The villagers gathered in the airport, a small building with no walls, to say a prayer of thanks for our safe arrival. They loaded our gear onto a tractor that took it directly to a small fishing boat, which would take us across the lagoon to the other side of the atoll. Our accommodations were two small bungalows sitting directly on the shore of the lagoon.

By the time we unloaded the boat, it was noon local time. We got to work unpacking the equipment that we had shipped there prior to our arrival and started assembling the station and building antennas. The assembly continued into Wednesday until we were hit with storms that brought severe winds. Aside from losing valuable setup time and having to rebuild an antenna that had blown over, we were very fortunate that there was no major damage.

Thursday was full of antenna work, repairing the small damages from the storm and building the rest of the VDAs (vertical dipole arrays). By sundown on Thursday the station was assembled and the antennas, aside from the 30m and 160m, were set up and tuned. We positioned the 10, 12, 15, 17, and 20m VDAs as close to the salt water as possible, placing sandbags in the coral reef to anchor the guy wires. CrankIRs covered 30, 40, and 80m, and we used an inverted-L for 160m.

The two main stations that would be on the air around the clock consisted of Elecraft K3s with FlexRadio PGXL amplifiers, with a third station of another K3 with a KPA500. The 6m station was a KX3 running 10 watts.

The experience level of our team varied widely. Rob, N7QT, has been on over two dozen DXpeditions, while I was on my very first and learning everything from the ground up. From discovering the strategies of antenna placement to a whole new propagation chart, every moment offered a unique learning experience.

We spent Friday morning troubleshooting issues with the network and equipment. By early afternoon we were QRV. We ran into our first issue when we found that the high-power band pass filters for 12m and 17m were bad. It was impossible to operate on those bands without causing immense interference to the other operators. It was possible to work FT8 on 12m and 17m at the same time, but CW and SSB were not viable options.

Other than a few network issues with Starlink and a mishap when one of our power strips caught fire, the first few days went smoothly and the number of contacts in the log steadily grew. All three stations were in constant use, while the fourth station monitored 6m for any possible openings.

Halfway through Friday night, the village power plant lost power. We had experienced several days of rain and overcast skies, and the backup generator for their power plant was not functioning properly. Unfortunately, the technician that usually services the power plant had just left for vacation in New Zealand. After half a day of troubleshooting, they found a temporary solution and our power was restored.

During the outage, we finished assembling the 30m VDA and set up the 160m inverted-L, which immediately proved to be a popular band. On Monday, Murphy’s Law struck again. We lost all audio on one of the K3s, meaning we were down to two stations plus the 6m monitor. Our operating schedule was built around two stations running 24/7, with the third station available for anyone to use during their off time. Although it was not a critical issue, it significantly slowed our QSO rate.

After another day of cloudy weather with more rain, the solar power bank was running low. One of the villagers went out early Tuesday morning to turn on the backup generator and then went home. An hour or two later, they discovered the backup generator was on fire. This included the building that also held the transformers which fed the village grid as well as the switch that controlled the power source—either the solar panels and batteries or the backup generator—that was feeding the grid.

As the villagers assessed the situation, it became evident that the damage was far too critical. The parts needed to restore at least the solar power needed to be shipped from New Zealand. They were estimating that a replacement backup generator would take up to six months to arrive on a cargo ship. The villagers set up a schedule to share the few small generators they had to run the freezers and keep food from spoiling in the heat. They apologized to us over and over for the premature end of our operation. There was nothing we could do but make the best of the time we had left on the atoll.

Adapting to daily life without power was nothing new to me since I spent most of my growing up without electricity in the Amish communities. After it became clear that there would be no further operating, we spent much of the remaining time learning about the unique culture and economy of Manihiki. Our host, Kora of Kora Pearls, took the team on a complete tour of his black pearl farm, from diving for the oysters to harvesting the pearls and re-seeding.

One evening we were invited to help lay reef nets to catch milk fish. The nets were placed downstream, and we walked shoulder to shoulder in the shallow water chasing a shoal of white milk fish into the nets. It was a very quick and efficient way to harvest hundreds of fish at once. The whole village showed up at the harbor to help clean the catch, eating them raw as they worked. It was enough to feed everyone for dinner with much to spare.

To me the most intriguing fishing adventure was when we ventured out into the ocean in a small aluminum boat to catch flying fish one night after dark. One fellow sat in the front on the bow, wearing a helmet with a searchlight attached and brandishing a net on the end of a long pole. The fish, attracted to the light, would jump out of the water, some flying for several yards! Hundreds of black-tipped sharks followed close behind, often crashing loudly into the sides of the aluminum boat as they fought for the stray fish. We shared the catch with families from the village and roasted the fish over an open fire.

We attended the local church on Sunday, which proved to be a fascinating cultural experience. We received a warm welcome and enjoyed the rich vocal music that filled the room. Even though most of the service was spoken in the Rakahanga‑Manihiki dialect, they translated parts of it into English for our benefit. Brian and Rob helped out around the village with several projects, including repairing an old generator. They were amazed at the locals’ ability to complete repairs using the very limited materials they had and the meager tools available.

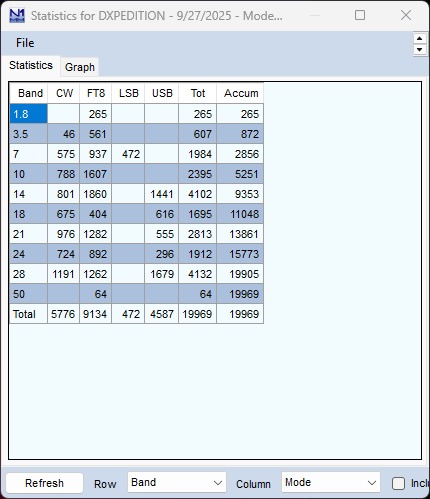

We disassembled the station and antennas and repacked the bins to prep for shipping the equipment back to the U.S. Even though it was an extremely unfortunate situation that forced us to QRT early, we are thankful for the operating time we had and all of the contacts that were made. Over the span of five days, we logged 20,290 QSOs, with 10m being the most popular band owning over 4,000 QSOs, followed closely by 20m.

Although the activation came to an abrupt and unexpected conclusion, I gained an invaluable amount of knowledge, experience, and skills during my time both on and off the air. It was an eye-opening experience from start to finish, and I have a deep respect for DXpeditioners after witnessing the sheer amount of time, energy, finances, planning, headaches, and flexibility it takes to pull off operations like these—done in an effort to give back to the hobby and to become the DX for our fellow hams.

My favorite contact during the DXpedition was a QSO on 10m with my dad and mom over 6,000 miles away in the backwoods of Kentucky. Another highlight was working Bob, W9KNI. This was a truly memorable full-circle moment, considering that my fascination for and love of DX was first sparked many years ago from reading his books, “The Complete DXer” and “A Year of DX”.

On Tuesday, October 21, we reluctantly left our new friends (and the fish and coconut diet) to repeat the same journey in reverse. We loaded our gear onto a boat, sailed across the lagoon to the airport, and took off for Rarotonga, where we went our separate ways. Shortly after our departure, we heard that Manihiki had received the parts needed to repair the solar panel transformers. The village now has power on sunny days, with further improvements in the works.

Even after two weeks full of chaos and adventure, I still had perhaps the most stressful part of the journey ahead—more than 35 hours of flight time with six layovers, traveling from the South Pacific to the Caribbean. I began my race against the clock to reach PJ2T in time for CQ WW SSB. Stay tuned for an upcoming article with a closer look at the youth contest crew operating from PJ2T.

Thank you to DX Engineering for supplying the team with hundreds of feet of coax and connectors. My deepest gratitude goes out to all who contributed to making this trip financially possible for me. Thank you! The next DXpedition is already in the works with more updates coming soon.