Editor’s note: OnAllBands is pleased to post a series of articles written by accomplished amateur radio contester and DX Engineering customer/technical support specialist Kirk Pickering, K4RO. The articles, originally published in the National Contest Journal and updated with current information, offer valuable insights for both contesters new and old.

Dealing with QRM

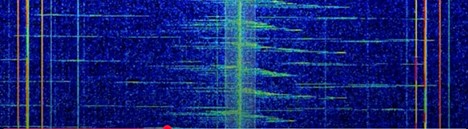

Anyone who has spent some time operating radio contests has probably been engaged in a frequency fight at one time or another. Particularly during low sunspot years, only one or two bands will be open at once, and the crowding can get intense. Probably the worst case is 20-meter phone during a sunspot minimum, when it seems like the entire contest community worldwide is packed into a single band. It’s not unusual to hear two or even three contesters calling CQ on the same frequency simultaneously under such conditions.

Consider that the 20-meter phone band is only 200 kHz wide, there are less than one hundred 2 kHz SSB “channels” available, and less than seventy 3 kHz SSB channels available. There is simply not enough room for everyone to have a “clear” frequency.

I recall the 2006 WPX SSB contest, where a team of TCG operators were operating Multi Single from K4JNY’s station in East Tennessee, using the call sign KM9P. For the first 20 straight hours of the contest, we were calling CQ on 14225.30 kHz. Contesting Hall-of-Famer Fred Laun, K3ZO (SK) was calling CQ on 14225.00 kHz. We were 300 HERTZ apart, essentially on the same frequency. We could hear Fred, and I suspect that Fred could hear us. The entire contest was basically on 20 meters, and it was a complete madhouse. There was just nowhere to go on the band.

To the casual observer, it might have seemed appalling that we were operating so close to each other. Yet as the hours went by, we were both putting QSOs in the log at a good rate. We did not want to operate on top of each other, but this was an extreme circumstance, and there really was nowhere else to go. Every frequency had two or three stations calling CQ on top of one another. The proof was in the pudding. K3ZO worked through our QRM and that of other stations all weekend to win the USA SOHP category that year. Meanwhile, the KM9P crew worked through the QRM on our end to win the USA Multi Single category.

Note that this was an extreme case of two big gun stations with highly skilled contesters, and no other bands were open or useful. Typically, contesters will find it more productive to find a clearer frequency to call CQ if at all possible. This is especially true if we are not one of the loudest signals on the band. One time I had finished a weekend of operating the CW Sweepstakes in the QRP category. The longest I was able to hold a run frequency was typically 10 minutes. Usually after 10 minutes or so, a stronger station would come by and push me away.

Does Might Make Right?

Some years ago on the CQ-Contest reflector, there was a discussion about frequency fights, and many folks weighed in on the topic. Back then, Fred made a comment that surprised me at first. He said: “As my dear departed and deeply missed mentor W3GRF always said, ‘It’s a listening contest as well as a sending contest.’ One measure of contest skill is the ability of a person to copy weak signals through heavy QRM. I reserve the right to decide for myself what bandwidth I need to run stations successfully. I don’t allow someone else to make that decision for me. If someone considers themselves to be my equal in operating skill, they should be able to put up with the same amount of QRM I’m willing to.”

It took me a while to truly understand what Fred was saying. Each operator has to learn for themselves how much QRM they can tolerate and then operate accordingly. In a sense, might does make right in contests, but it is not always simply a matter of who is louder. Typically, the “winner” is the station who is able to generate more QSOs, as evidenced by more stations calling him. I was even more surprised to learn back then that Fred operated CW contests with 2.4 kHz filters, and SSB contests with a 6.0 kHz filter. No wonder he was a frequent winner of the Dayton CW pileup competitions.

Fred had trained his brain to pull calls out of the worst QRM, and it showed in his results. So does this mean that it’s okay to jump upon a weak station’s frequency and start calling CQ? While there are some operators who justify such frequency “scrumming,” most operators will instead keep tuning and try to find a “hole” in the band to call CQ. Each individual has to make choices and develop their own operating style.

I’ve heard one top operator declare, “I have no friends once the starting bell rings,” while other operators place some emphasis on courtesy over conflict. It is unacceptable to purposely generate key clicks or over-drive your transmitter in order to create QRM. Such practices should be heavily frowned upon. Be sure to check with a trusted friend on the air to confirm that the settings you use during a contest sound okay.

Know When to Hold ‘Em

The choice of whether to stay and battle or QSY, like a lot of things in contesting, depends on the situation. One wants to be aggressive in keeping a productive CQ frequency, while not wasting too much time over an unproductive one. The best way to hold a frequency is to keep making QSOs on that frequency. If I have a good productive run frequency, I will generally fight hard to keep it. If we have a good signal into the target area and the rate is staying up, it makes sense to stay put and keep on putting QSOs into the log.

I might QSY from a run frequency for a number of reasons, though. If I’ve just arrived and the frequency is clearly still in use, I’ll QSY. If I’ve been there a long time and the rate is dropping or the propagation is going against my favor, I might QSY. Sometimes a frequency that was clearly “ours” can become someone else’s as the sun’s terminator sweeps across our continent. Two stations productively using the same frequency toward different target areas can wind up on top of one another as propagation changes.

If I can move a multiplier, I might QSY. If I think I can make higher rate by searching and pouncing I might QSY. I might even leave a perfectly good run frequency to make sure that I don’t miss any multipliers during a band opening. The more contests that we operate, the more we develop an instinct for finding and keeping run frequencies. In the beginning, the simplest rule of thumb is to go higher in the band to find clearer frequencies.

Save Your Ears

I don’t believe that I have ever operated a contest without headphones. A good pair of headphones is an essential tool for CW and SSB contesting.

I learned that many top RTTY operators also use headphones, as they can tune quite accurately by ear. We as contesters must work stations over a very wide dynamic range, and sometimes the receiver gain is turned up very high to copy the weakest signals. The problem occurs when a loud station calls while the gain is way up. Even with AGC circuits enabled, our ears can be subject to some high sound pressure levels via the headphones. Try to remember to keep the gain turned down as much as possible. Besides saving your ears, it will also lower your fatigue factor.

That’s all for this time. Please remember to send me your questions or comments.

73