Editor’s note: OnAllBands is pleased to post a series of articles written by accomplished amateur radio contester and DX Engineering customer/technical support specialist Kirk Pickering, K4RO. The articles, originally published in the National Contest Journal and updated with current information, offer valuable insights for both contesters new and old.

***

Hello and welcome back to Contesting 101. Dayton Hamvention® 2025 is underway! It’s an event that always promises to be a fine weekend among contesters. Please don’t hesitate to send me your questions or comments. I can be contacted at k4ro@k4ro.net.

Assistance

The contesting email reflectors have had much traffic lately regarding various forms of “assistance” available to the contest operator. While some argue that assistance means everything from memory CW keying to computer logging, most contest rules have a fairly common definition. Anything that tells the operator WHO is WHERE and WHEN is considered assistance.

Whether the information is coming from a packet cluster network, a wideband decoding device, or a buddy with another radio, the ultimate result is someone or something else locating and identifying signals for you. Referring back to our first OnAllBands column, the ability to identify signals is one of the most fundamental and important skills a contest operator needs to have in their arsenal. Particularly for the newcomer to contest operating, tuning the bands and identifying signals are crucial skills to develop. Using spotting assistance deprives us of the challenges and rewards of finding and identifying stations on our own.

My recommendation is for the new contest operator to not use any form of spotting or DX alerting assistance. New operators will benefit far more by developing their own tuning and identifying skills. When we learn to tune the bands on our own, we typically find it far more satisfying (and fun!) than having someone else do it for us.

The Importance of Calling CQ

In the last column, we covered the basics of Search and Pounce (S&P) operation. S&P operation involves finding stations which are calling CQ and then calling them to initiate a contest QSO. In order for a QSO to take place, obviously someone must be calling CQ! Learning to call CQ effectively is one of the most important skills a contest operator must develop. Many new contest operators may never call a single CQ. They might spend the entire contest in the Search and Pounce mode. There is nothing wrong with this style of operation. It can be quite fun and even relaxing. However, when the contester is looking to make more QSOs and raise their score, calling CQ is the only alternative.

One myth is that only high-powered stations with massive antenna systems can call CQ. The fact is, even a QRP station can effectively call CQ in a major contest with high-power stations everywhere, such as the ARRL November Sweepstakes.

Consider that the majority of participants in a given contest are casually tuning the bands and answering CQing stations. They are not calling CQ themselves—they are only answering stations. It follows logically that the only way to work these stations is to be calling CQ as they tune by our frequency. If we aren’t calling CQ, we won’t work many of these casual S&P operators. If we want to score well, we had better be working these casual S&P operators. Our competition likely is.

Getting Up the Nerve

Most contest operators experience some fear during their first forays into calling “CQ Contest.” One of the challenges when calling CQ is that we have no control over the signals which come back in answer to our solicitation. This is different than S&P operation, where we get to decide whether a station is workable before calling them. The operator calling CQ must be ready to copy whatever comes back in reply—whether the signal is S9 and Q5 or barely above the noise level. For this reason, there is a level of anticipation and accompanying adrenaline rush that is unique to calling “CQ Contest.” In fact, this rush from “running” stations is so compelling that some operators go to great lengths to maintain that capability, even traveling to distant lands to operate contests (or DXpeditions) where the pileups almost never stop!

The same thing that makes running stations so exciting also makes it challenging. Some operators don’t call CQ because they think they might not be able to handle the ensuing stations which may answer. Here are some suggestions for overcoming the “stage fright” of calling CQ Contest. First, spend some time listening to a good operator run stations. Pay close attention to how they handle really weak callers or multiple simultaneous callers. You’ll find that it’s really not rocket science. After some time listening, imagine yourself in the operator’s chair and picture how you would respond to each current caller. Practice “running” the stations that you can hear, as if you were at the microphone or key. Before long, you should start to feel some comfort with the process and get a feel for the rhythm.

For operators in North America, I feel that the best contests for learning to call CQ are the NCJ-sponsored North American QSO Parties. The NAQP contests offer an excellent training ground for both S&P and running skills. The 100-watt power limit and multipliers-by-band scoring rules allow plenty of room for the novice contest op to experience running stations. Try calling CQ in the next NAQP contest. You might discover for yourself why “rate is great!”

When and Where to Call CQ

The short answer is, whenever and wherever you can! In most rate-oriented contests like NAQP or the CQ World Wide WPX Contest, for example, you are almost always better off calling CQ if you have a decent signal. In a 100-watt contest like NAQP, almost everyone with an efficient antenna has a “decent” signal. The time and place to call CQ is basically any time and any place that you can get answers.

S&P can produce a pretty good rate on a fresh band (one you have not operated on yet.) The problem is that after you have worked a band dry with S&P, the rate starts to drop. If folks are coming right back to you on the first call, you will probably be better off running than staying in S&P. Let your rate meter be your guide. If a band is open well, it is usually possible to sustain a better rate by calling CQ than by searching and pouncing.

Finding and establishing a CQ frequency is another skill that takes some time to get comfortable with. Newer operators tend to require a little more breathing room to identify stations calling, while the seasoned vets can hear through unbelievable QRM.

One good way to find a CQ frequency is to S&P until we find a “hole.” Depending on band conditions and the type of contest, there might be many holes to choose from, or there may be none at all (the band is jam packed). When we find a hole, listen for the length of a typical QSO to make sure it really is a hole. It might not be a hole—we might not be able to hear one side of the QSO. After determining that the frequency is indeed clear, we will send QRL? or ask, “Is the frequency in use?” If there is no response, it’s time to call CQ Contest! Take a deep breath and prepare to copy any callers. Be patient. If you don’t get any answers after a few CQs, don’t give up. Sometimes it takes a while for a frequency to “warm up.”

One of the interesting aspects of calling CQ is that we can generate an “audience” of callers. Search and pounce operators will pause to listen to clean and efficient technique. If we are working stations quickly and smoothly, many stations may queue up to call us. Understanding the current audience is one of the keys to successful CQing.

Think LOUD and CQ Frequently

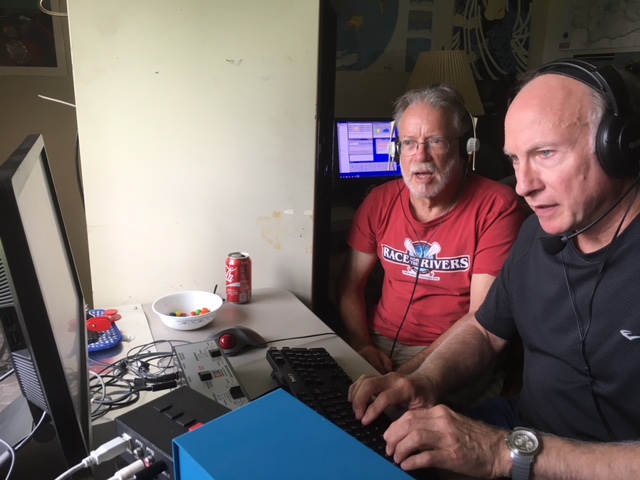

I remember operating my first Field Day years ago and watching K4AMC, K0EJ, and W9WI running stations. It seemed like they were calling CQ nonstop, with very short breaks between (like 3 to 5 seconds). They were also getting answers nonstop. I watched the rate meter and was amazed at the number of stations going into the log per hour. These guys knew what they were doing. After a while, it was my turn to take the key. Within a short time of my taking over, the rate meter started to drop like a lead balloon.

K0EJ nudged me and said, “You can’t be the loudest signal on the band if you’re not transmitting.” I think he may have heard that from W1ZM. That simple statement told me two important things. First, I had to believe that our signal was LOUD. I had to believe that other stations could hear us easily, with confidence. Second, these stations would not hear our loud signal if I was not transmitting a CQ! I started calling CQ a lot more frequently, and before I knew it, the rate meter went back up where it was before.

The gaps between CQs only needed to be long enough for a station to answer within a reasonable time. If there was no answer, it was time to call CQ again. In a future column, we will discuss some of the finer points of calling CQ. For now, remember to keep your calls clear and succinct. Contesting rewards the efficient operator. Here are some examples of how to call CQ. Note that it is not necessary to add the word “contest” or “test” to the end of a CQ, though some operators still prefer to do so.

- CW: CQ TEST K4RO K4RO

- RTTY: CQ TEST K4RO K4RO CQ

- Phone: CQ Contest K4RO Kilo Four Romeo Oscar

I hope to hear you calling “CQ Contest” during future contests like the NAQP.

Please don’t forget to send me your questions or comments. I look forward to hearing from you.

73 -Kirk